We Still Practice our Ojibwe Culture

Ceremonial dancing is one aspect of Ojibwe culture and tradition.

We still have totems or clans, what we call odoodeman. Clan membership passes through the male lineage, from the father’s clan. It’s still considered taboo to marry someone from the same clan.

Traditionally we lived by cultivating corn and squash, by hunting and fishing, and by harvesting wild rice. Each September we celebrate with a Wild Rice Festival. We still gather syrup from the sugar maple trees on the reservation.

We are known for our sacred birch bark scrolls, and our Midewiwin Society is the keeper of detailed scrolls of oral history, songs, events, geometry and mathematics. We are known for our birch bark canoes. We often fished using nets, but at night we would fish from our canoes. We would attract fish with a torch made of tightly twisted birch bark. When fish came near the light, we would catch them with a fishing spear.

This is how we came to be known as Lac du Flambeau. Upon seeing us in our canoes at night, the French trappers would refer to us as lac du flambeau – lake of the torches.

We call ourselves Waaswaaganing, which means Lake of Flames in Ojibwe.

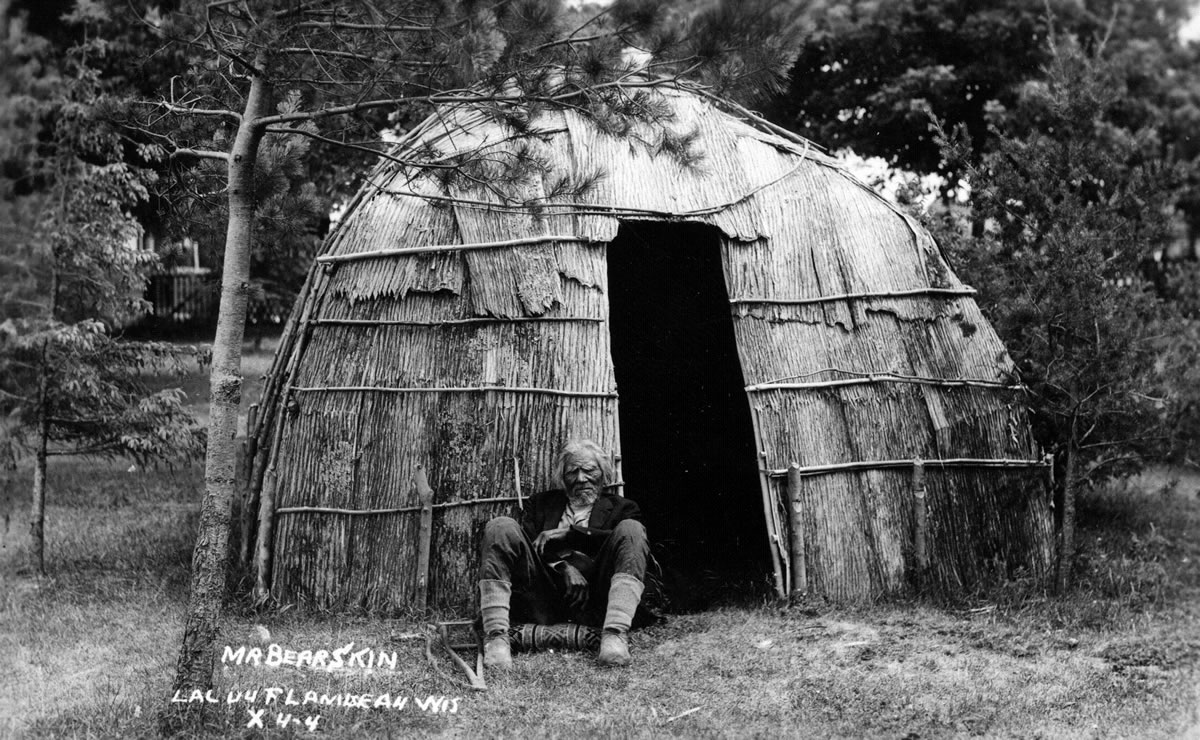

During summer months, we enjoy dancing and singing at niimi’idimaa, or social pow wows. We still use the sacred sweat lodge for purification. The lodge is a circle built upon Mother Earth, and is made of willow branches, and canvas or blankets. The lodge includes a sacred fire for heating the rocks, and an altar for the sacred pipe and medicines. In addition to water, medicines include tobacco, sage, cedar and sweet grass. The sweat is a supreme communication with the Creator.

Incredible Journey of Chief Buffalo

In the late 1840s, government agents in Washington began efforts to remove the Lake Superior Chippewa people from their homeland. Officials changed the location of the treaty payments to a place in Minnesota, which would require a journey of 150 miles by canoe and on foot. The result was the death of hundreds of people because of delayed payments, tainted food, disease and the onset of winter.

This became known as the Sandy Lake Tragedy.

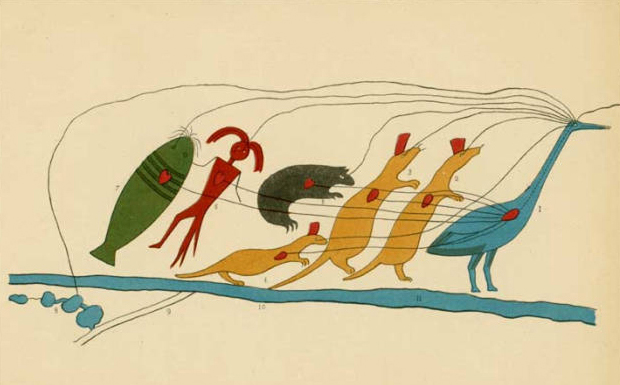

Kechewaishke (Chief Buffalo), principal chief of the Lake Superior Chippewa, was determined to do whatever was necessary to protect his people. On April 5, 1852, he started an incredible journey to Washington, along with sub-chief Oshaga, four other Ojibwe, and interpreter Benjamin Armstrong. In addition to their provisions, Kechewaishke brought a petition to give to President Millard Fillmore. The petition was a pictograph on birch bark that included five Ojibwe totems, or clans. These totems – a crane, marten, bear, man and catfish – represented the Ojibwe Tribes of Northern Wisconsin and Upper Peninsula area. Lines from the heart and eye of each animal to the heart and eye of the crane denote that they are all of one mind.

After meeting with President Fillmore, the President announced that the removal order would be canceled, and that another treaty would establish permanent reservations for the Ojibwe in Wisconsin.

Today, there are two marble busts of Buffalo in the U.S. Capitol – a marble bust for the Senate side and a bronze bust for the House side of the Capitol. A U.S. Senate document says, “This formidable Native American was also called Great Buffalo, and the adjective was clearly deserved.”

Dugout and Birch Bark Canoes

For thousands of years, dugout and birch bark canoes were an important means of transportation for us. We call the dugout canoe mitigo-jiiman, which means “wood canoe.” Two men would use small fires and stone or metal tools to make a dugout canoe. This would take around 10 days.

In our more recent history, we traveled in birch bark canoes. We would cut the heavy bark from a large birch. This was done in early spring when the bark was most easily removed from the tree. Cedar was used for the frame around the top, the ribs, and the thwarts (the horizontal bars that connect the frame). The bark was stitched together using split roots of the tamarack tree, or sometimes spruce. To make the canoe watertight, gum resin was collected from evergreen trees and boiled in a kettle to make pitch. Charcoal powder was added to make the pitch firm. The pitch was applied to the seams of bark with a wooden spatula. The typical canoe was about 12 feet long and three feet across the middle. But the size varied according to use – smaller canoes were designed for speed, and larger canoes were designed for carrying belongings and trade goods. The largest canoes carried 10 people.

In May of 1980, divers were exploring the bottom of Flambeau Lake. Suddenly they saw a dugout canoe sticking out of the mud and silt. The canoe was found near the site of the last major battle between the Chippewa and the Dakota, which occurred on Strawberry Island in 1745.

This rare, 24 foot dugout canoe is on display at the George W. Brown, Jr. Ojibwe Museum in Lac du Flambeau.